Morphy showed promise as a chess player from a very young age. He seems to have learned the game from watching his father and uncle play. His relatives and their business associates were the leading players of New Orleans, Louisiana. Young Paul was already beating them by the time he was ten years old.

Morphy had a terrific memory and excelled in school. Before he reached the age of 21, he had finished all the schooling necessary to embark on a career in the practice of law, but he could not be admitted to legal practice until he reached adulthood. Hence, he took some time to play chess. He competed in the First American Chess Congress (1857), which he won, and then departed for Europe, hoping to play the leading masters there.

He won matches against several players in England, and also participated in chess exhibitions, such as simultaneous play where he played many games at once. His only disappointment was that Howard Staunton, England's top player, could find neither the time nor the will to arrange a match with Morphy.

Morphy then went to Paris, France. He intended to continue to Germany and Austria, but grew ill during the passage from England to France. He spent the fall 1858 in Paris, and then extended his stay through the winter on the advice of his physician. During the Christmas holiday, Adolf Anderssen traveled to Paris for the much anticipated match between Europe's top player and North America's. Morphy won the match.

|

| A Scene at the Italian Opera, Paris 1856 |

Morphy loved music and was a frequent guest of the Duke of Brunswick at the Italian Opera. The Duke's private box was on the edge of stage. It was so close that when the Duke and his guests conversed too loudly, the actors thought the conversation there was part of the performance. The Duke kept a chess set there. When Morphy attended the opera, he was seated with his back to the stage so that the Duke and one or more of the Duke's other guests could consult in a chess game against the chess master while listening to the music. Morphy played several games in this manner, but the moves of only one such game has been preserved.*

The Lesson

Beside the demonstration chess board, I wrote:

Development

mobility

coordination

vulnerability

I asked students to repeat these words and to remember them. I explained that central to the idea of development was mobilizing your pieces. We discussed the relative mobility of a knight or bishop at the center of an empty board versus one on the edge of an empty board. A piece that can move to more squares is more mobile. I explained that good chess players labor to make their pieces work together in harmony while they are improving each piece's mobility from the limits of the starting position. Such piece coordination is necessary to exploit vulnerabilities in the opponent's position. It is important in the beginning of a chess game, and throughout, to attend to the security of one's king, and to avoid leaving pieces where they can be captured without consequence. Reducing one's own vulnerabilities is important, as is exploiting those vulnerabilities that might be created when an opponent fails to do the same.

We then proceeded to go through Morphy's game played at the opera against the Duke of Brunswick and Count Isouard. I suggested that there is no reason why young players could not memorize the entire game.

Morphy, P -- Duke and Count

Paris, 1858

1.e4

I urge young players to play this move with the White pieces at least one hundred times before they consider any other first move. This move stakes a claim to the center and increases the mobility of four White pieces, most notably the queen and bishop.

1...e5

This move is as good for Black as for White.

2.Nf3

Attacks Black's e-pawn, creating a problem for Black to solve.

2...d6

Philidor's Defense is one of several ways to address the threat of White's second move.

3.d4 Bg4

White struck at e5 a second time. Black opted to pin White's knight, indirectly protecting the vulnerable e-pawn. See "Lasker's Rules" for some caveats regarding Black's third move.

4.dxe5 Bxf3 5.Qxf3 dxe5

Black avoided losing a pawn by capturing the knight before recapturing on e5. White threatened to escape the pin with an exchange of queens.

6.Bc4

White threatens checkmate in one.

6...Nf6 7.Qb3 Qe7

This move not only defends against the loss of the f7 pawn, but also looks ahead tactically at White's threat to the rook on a8. However, it blocks the bishop on f8. Black's lack of kingside piece mobility will endure through the rest of the game. Being unable to mobilize the kingside also keeps Black's king in center where it is more vulnerable. Morphy exploits these weaknesses brilliantly.

8.Nc3!

Rather than taking the free pawn, which would permit Black to force the queens off the board and allow them to mobilize their kingside, Morphy increases the pressure on Black's position. Morphy's move aims at improving piece coordination rather than wantonly grabbing material.

8...c6

Black defends the b-pawn, but this move neither improves the mobility of Black's pieces, nor improves piece coordination.

9.Bg5

Morphy pins Black's knight against the queen.

9...b5

The Count and Duke seek to drive back one of White's pieces.

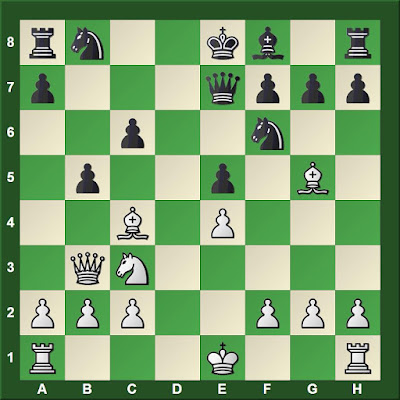

White to move

10.Nxb5!

It is much easier to sacrifice material when two of the opponent's pieces are mere spectators. It is possible that Morphy saw all the way to the end of the game from this position.

10...cxb5 11.Bb5+ Nbd7 12.O-O-O

Having pinned the second knight, Morphy attacks the knight on d7 a second time. Rd1 is less effective because it does not permit the other rook to come to d1 as rapidly. In addition, by castling, Morphy reduces the vulnerability of his king. Although, Black's pieces are tied down so thoroughly that there is little they would be able to accomplish exploiting vulnerabilities.

In this position, we see that almost all of White's pieces are working together harmoniously from active squares where they are mobile. Black's pieces are unable to move because they are hemmed in by other pieces, or they cannot move without disaster due to pins.

12...Rd8 13.Rxd7!

Morphy sacrifices the exchange in order to maintain a pin on d7.

13...Rxd7 14.Rd1 Qe6

Black finally steps out of the pin on the queen.

15.Bxd7+ Nxd7

Black could have given up the queen to avoid checkmate.

White to move

16.Qb8+ Nxb8 17.Rd8#

*Preparing to write this blog post, last night I reread the relevant portions of Frederick Milnes Edge, Paul Morphy the Chess Champion (1859); Max Lange, Paul Morphy: A Sketch from the Chess World (1860); David Lawson, Paul Morphy: The Pride and Sorrow of Chess (1976); and Philip W. Sergeant, Morphy's Games of Chess (1957). In addition to these four books, I read again Edward Winter, "Morphy v the Duke and Count," Chess Notes (updated 20 March 2014); and my own previous blog post, "The Opera Game" (22 March 2015).

No comments:

Post a Comment