The first game was not particularly eventful. Although Carlsen managed to create weaknesses in Karjakin's pawn structure, the challenger managed to hold the position without too much pain. Looking at the final moves from my position as a class player, however, I did not know at a glance whether swapping the last pair of minor pieces could give either player an advantage in the pawn ending.

Had Karjakin played 40...Bxd4, would the game be drawn as well? Grandmasters probably understand the resulting pawn position at a glance, but many other chess players could do well to play it out against a friend or computer.

Carlsen's play with Black in game two deprived Karjakin of any real chance for an advantage.

Ruslan Ponomariov, who wrote the annotations to the first two games for ChessBase, thought that Carlsen could have presented Karjakin with a tactical problem to solve with a different move 26, but Karjakin probably would have seen the trick clearly.

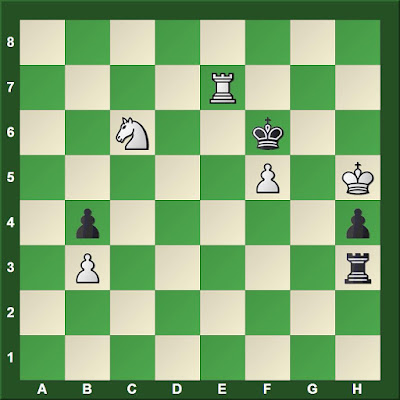

In the third game, Carlsen secured an advantage and then pressed hard for a win. The ending generated a lot of interest around the world. Yasser Seirawan was at a dinner in Saint Louis, where he joined Viswanathan Anand, Hikaru Nakamura, Veselin Topalov, and Fabiano Caruana following the game on Caruana's smartphone. Seirawan's annotations for ChessBase presented a drawing opportunity missed by Karjakin from this position.

Black to move

|

| After 70.Nc6 |

Seirawan's analysis, presenting the ideas of four other Grandmasters who "out-rated" him, after 70...Rc3!! is worth checking out at the link. Credit Anand for convincing the others that Karjakin could hold.

Chess fans following the game with the aid of engine analysis quickly spotted Carlsen's decisive error as he was pressing for a win in game four. However, Carlsen thought the line he played was winning. It took many more moves before Carlsen's winning ideas had been proven illusions.

Black to move

|

| After 45.Nd1 |

Karjakin was slightly better in game five and spent a lot of time in this position, which my advanced students were watching on the demo board at chess club while it was taking place.

Black to move

|

| After 42.hxg4 |

Gmae six was the least interesting game, except to those who seek to understand the Marshall Gambit and its variants when Black needs a draw against the Spanish. In the annotations for ChessBase, Tiger Hillarp Persson points out Karjakin's method and the computer's method of securing a clear draw from this position as White.

White to move

|

| After 20...Rfe8 |

White to move

|

| After 15...O-O |

After failing to get an advantage in the two shortest games of the match, and his two consecutive Whites, Karjakin explained, "it is better to play well than to play with White." In game eight, he broke the historic run of draws (the longest in a world championship match sine 1995), winning with the Black pieces.

Both players made errors in the time scramble just before move 40. Carlsen made a bad move in a bad position and then Karjakin missed the strongest continuation. Play went on into another hour.

White to move

|

| After 48.Nd3 |

In the ninth game, Sergey Karjakin might have had a chance to put Carlsen away and gain the upper hand in the match.

White to move

|

| After 38...Ne7 |

In the tenth game, Karjakin missed a forced draw early in the game and then suffered a long time.

Black to move

|

| After 20.Nd2 |

Karjakin finally cracked after defending a difficult endgame for many hours, allowing Carlsen to even the score.

The number of positions arising in this match, which I would have mis-evaluated had I not known who was playing were significant. In many positions, Karjakin was able to keep tension when I thought he was clearly worse. I don't think a couple of the positions you presented above were the most difficult to evaluation (but you are listing critical positions here, I understand). The ending for game one is straightforward enough, and I'm downright shocked that Karjakin didn't see the forced draw in game 10. in fact, unless he said he missed it, I can't believe he didn't see it, but rather chose to play to win. As a player whose barely cracked 1800, I saw the drawing line as soon as I saw the position. This would be a Kramnik-esque moment of blindness, not exactly akin to Fritz's mate-in-one vs Kramnik, but very similar. Unless there is a clip of Karjakin saying he didn't see it, I can't believe it.

ReplyDeleteGreat blog post.

Karjakin said in the press conference that he missed the draw. He saw Nxf2, of course, but not the whole line. Starts about four minutes in: Game 10 Press Conference

Delete